More companies than ever have made a public commitment to the transition to Net Zero, but it remains incredibly difficult to quickly and easily distinguish the good from the bad. Even skilled operators can be tricked or misled by a plan that may look good, but doesn’t meet the simple requirement of avoiding as much climate damage as possible, in as short a timeframe as possible.

This is meaningful for investors, in particular. A clear declaration of how climate risk will be managed is profoundly valuable information for investors, as well as for regulators. The risk of bad transition plans sticks out in a variety of ways; both through the potential losses for exposed companies and diverse portfolios, but also increasing regulatory requirements to decarbonise businesses in step with science-aligned temperature pathways.

What has become clear in the half-decade since the rise of net zero has been some consistency in the methods used in the worst, most misleading transition plans.

Here’s how to spot a good one.

The climate benefits have to be real

Transition plans should be dedicated largely to stopping the release of greenhouse gases: the substance that causes Earth’s atmosphere to heat when added in large volumes. This means aiming to fully eliminate the burning of coal, oil and gas, and halt the release of methane from mining or agriculture.

Many transition plans use “intensity” targets that aim to reduce emissions per unit of revenue, or they fail to set targets for material direct emissions reductions and claim to compensate through the purchase of carbon offsets.

It can boil down to a simple question: does this plan result in the elimination of the vast bulk of greenhouse gas release? If not, the physical reality is that it is insufficient.

Urgency matters more than anything else

The 2022 “Integrity Matters” report, published by the High Level Expert Working Group convened by the United Nations, highlights the need for near term action in net zero commitments from non-state actors more prominently than other concerns.

The dynamic of climate change is such that emissions accumulate in the atmosphere – putting off action until the 2040s, for instance, means a higher amount emitted in the intervening years, and materially worse climate consequences as a result.

2025 matters far more for a transition plan than 2050, or 2040. The nearer the commitment to the present, the greater the integrity of the transition plan.

Accountability and transparency are must-haves

The UN “Integrity Matters” report details the need for non-state actors to fully disclose their emissions data, particularly in a way that isn’t packaged into a narrative but is rather produced in a standardised format. Independent, third-party review of emissions data is important, as is accessibility.

These data sets allow for accountability – ie, comparing actual emissions changes to targets previously set. Complete honesty on both counts demonstrates a genuine willingness to shift business models towards climate-compatible designs. However, efforts to hide emissions data or obscure tracking suggests a failure to engage.

A transition to clean

A business or an investment portfolio with a plan to transition away from fossil fuels, must clearly articulate where they are transitioning to. A comprehensive transition plan will address both sides of the transition, and state how the business is positioning itself to thrive in a greener and more just economy.

Evidence of a complete transition plan should include supporting the shift towards clean energy; whether through targeted lending or direct support for clean projects. This approach should also be applied throughout supply chains, by pressuring upstream and downstream value chains to shift in step to clean modes of operation.

Outside direct emissions

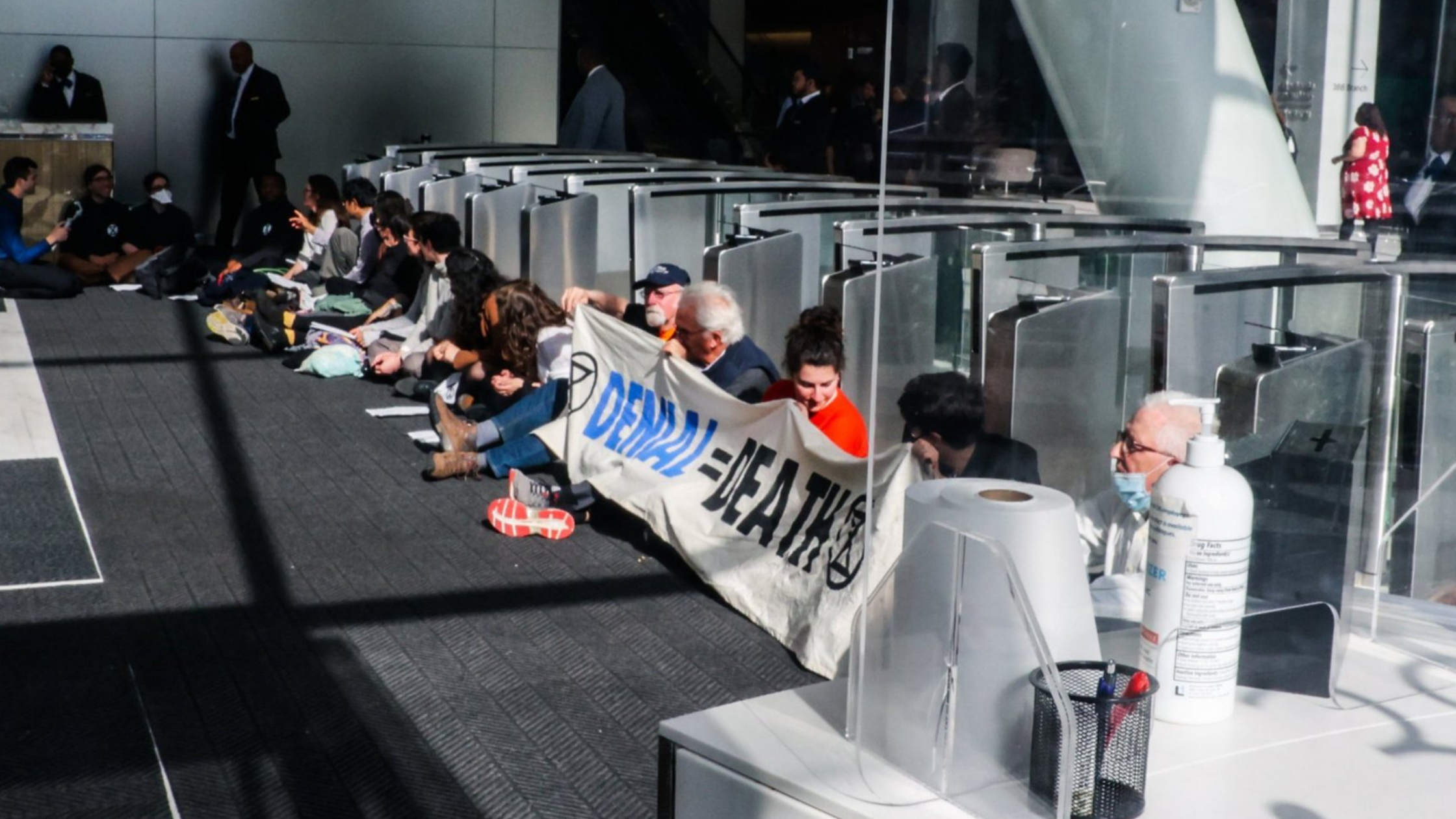

A company can have influence well outside its direct or indirect measured greenhouse gas emissions. An array of related factors have to be considered, disclosed and eventually addressed by companies purporting to have set a strong net zero target. These include:

- Ending support for fossil fuel production, processing and transport (eg through lending or insurance)

- Ending memberships with industry lobbying organisations that are acting against the best interests of climate, environment and sustainability.

- Considering issues of justice, equity and human rights

- Considering nature and biodiversity

A well-planned transition is good for business

Companies which publish a credible transition plan in good faith demonstrate prudent business planning. A recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the macroeconomic damages from climate change are likely to be six times larger than previously thought, with a 1% increase in global temperature resulting in a 12% decline in GDP. The transition to a low carbon economy is necessary, and ultimately inevitable. Investors should look to the quality of transition plans as a litmus test for the resilience of businesses in their portfolio to adhere to increasingly stringent regulations and navigate the financial consequences of a rapid global transition from fossil fuels to a clean economy.

Share